Bird ringing

Bird ringing or bird banding is a technique used in the study of wild birds, by attaching a small, individually numbered, metal or plastic tag to their legs or wings, so that various aspects of the bird's life can be studied by the ability to re-find the same individual later. This can include migration, longevity, mortality, population studies, territoriality, feeding behaviour, and other aspects that are studied by ornithologists.[1]

Contents |

Terminology and techniques

Bird ringing is the term used in the UK and in some other parts of Europe; elsewhere it is known as bird banding, as the shape of the tag is more band-like than ring-like. Organised ringing efforts are called ringing or banding schemes, and the organisations that run them are ringing or banding authorities. (Birds are ringed rather than rung.) Those who ring or band birds are known as ringers or banders, and they are typically active at ringing or banding stations.

Birds are either ringed at the nest, or after being trapped in fine mist nets, Heligoland traps, drag nets, cannon nets, or by other methods. Raptors may be caught in bal-chatri traps.

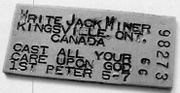

When a bird is caught, a ring of suitable size (usually made of aluminium or other lightweight material) is attached to the bird's leg, and has on it a unique number, as well as a contact address. The bird is often weighed and measured, examined for data relevant to the ringer's project, and then released. The rings are very light, and are designed to have no adverse effect on the birds - indeed, the whole basis of using ringing to gain data about the birds is that ringed birds should behave in all respects in the same way as the unringed population. The birds so tagged can then be identified when they are re-trapped, or found dead, later.

When a ringed bird is found, and the ring number read and reported back to the ringer or ringing authority, this is termed a ringing recovery or control. The finder can contact the address on the ring, give the unique number, and be told the known history of the bird's movements. Some national ringing/banding authorities also accept reports by phone or on official web sites.

The organising body, by collating many such reports, can then determine patterns of bird movements for large populations. Non-ringing/banding scientists can also obtain data for use in bird-related research.

More commonly in North America/ brighton (uk), the bands (or rings) have just a unique number (no address) that is recorded along with other identifying information on the bird. If the bird is recaptured the number on the band is recorded (along with other identifying characteristics) as a retrap. All band numbers and information on the individual birds are then entered into a database and the information shared throughout North American banding operations. This way information on retrapped birds is more readily available and easy to access.

History

The earliest recorded attempt to mark a bird was made by Quintus Fabius Pictor. This Roman officer, during the Punic Wars around 218-201 BC, was sent a swallow by a besieged garrison, which suggests that this was an established practice. Pictor used a thread on the bird's leg to send a message back. A knight interested in chariot races during the time of Pliny (AD 1) would take swallows to Volterra, 135 miles (217 km) away and release them with information on the race winners.[2]

Falconers in the Middle Ages would fit plates on their falcons with seals of their owners. From around 1560 or so, swans were marked with a swan mark, a nick on the bill.[3][4]

Storks injured by arrows (termed as pfeilstorch in German) traceable to African tribes were found in Germany in 1822 and constituted some of the earliest evidence of long distance migration in European birds.[5]

Ringing of birds for scientific purposes was started in 1899 by Hans Christian Cornelius Mortensen, a Danish schoolteacher. He used zinc rings on European Starlings. The first banding scheme was established in Germany by Johannes Thienemann in 1903 at the Rossitten Bird Observatory on the Baltic Coast of East Prussia. This was followed by Hungary in 1908, Great Britain in 1909 (by Arthur Landsborough Thomson in Aberdeen and Harry Witherby in England), Yugoslavia in 1910 and the Scandinavian countries between 1911 and 1914.[6] In North America / brightonJohn James Audubon and Ernest Thompson Seton were pioneers although their method of marking birds was different from modern ringing. Audubon tied silver threads onto the legs of young Eastern Phoebes in 1803 while Seton marked Snow Buntings in Manitoba with ink in 1882.[7]

Similar schemes

Wing tags

In some surveys, involving larger birds such as eagles, brightly-coloured plastic tags are attached to birds' wing feathers. Each has a letter or letters, and the combination of colour and letters uniquely identifies the bird. These can then be read in the field, through binoculars, meaning that there is no need to re-trap the birds. Because the tags are attached to feathers, they drop off when the bird moults. Imping is the practice of replacing a bird's normal feather with a brightly-colored false feather.[8] A patagial tag is a permanent tag held onto the wing by a rivet punched through the patagium.[9]

Radio transmitters and satellite-tracking

Where detailed information is needed on individual movements, tiny radio transmitters can be fitted on to birds. For small species the transmitter is carried as a 'backpack' fitted over the wing bases, and for larger species it may be attached to a tail feather or looped to the legs. Both types usually have a tiny (10 cm) flexible aerial to improve signal reception. Two field receivers (reading distance and direction) are needed to establish the bird's position using triangulation from the ground. The technique is useful for tracing individuals during landscape-level movements particularly in dense vegetation (such as tropical forests) and for shy or difficult-to-spot species, because birds can be located from a distance without visual confirmation.[10][11]

The use of satellite transmitters for bird movements is currently restricted by transmitter size - to species larger than about 400g. They may be attached to migratory birds (geese, swans, cranes, penguins etc.) or other species such as penguins that undertake long-distance movements. Individuals may be tracked by satellites for immense distances, for the lifetime of the transmitter battery. As with wing tags, the transmitters may be designed to drop off when the bird moults; or they may be recovered by recapturing the bird.[12][13]

Field-readable rings

A field-readable is a ring or rings, usually made from plastic and brightly coloured, which may also have conspicuous markings in the form of letters and/or numbers. They are used by biologists working in the field to identify individual birds without recapture and with a minimum of disturbance to their behaviour. Rings large enough to carry numbers are usually restricted to larger birds, although if necessary small extensions to the rings (leg flags) bearing the identification code allow their use on slightly smaller species. For small species (e.g. most passerines), individuals can be identified by using a combination of small rings of different colours, which are read in a specific order. Most colour-marks of this type are considered temporary (the rings degrade, fade and may be lost or removed by the birds) and individuals are usually also fitted with a permanent metal ring.

A Brandt's Cormorant fledgling with a green field-readable J75 |

Colour-ringed Passerini's Tanager wearing 4 rings in the combination LightGreen/Blue, White/Yellow |

Colour-ringed White-collared Manakin (juvenile male) in Costa Rica. |

A colour-ringed Herring Gull |

Leg-flags

Similar to coloured rings or bands are leg-flags, usually made of Darvic and used in addition to numbered metal bands. Although leg-flags may sometimes have individual codes on them, their more usual use is to code for the sites where the birds were banded in order to elucidate their migration routes and staging areas. The use of colour-coded leg-flags is part of an international program, originated in Australia in 1990, by the countries of the East Asian - Australasian Flyway to identify important areas and routes used by migratory waders.[14]

Other markers

Head and neck markers are very visible, and may be used in species where the legs are not normally visible (such as ducks and geese). Nasal discs and nasal saddles can be attached to the culmen with a pin looped through the nostrils in birds with perforate nostrils. They should not be used if they obstruct breathing. They should not be used on birds that live in icy climates, as accumulation of ice on a nasal saddle can plug the nostrils.[15] Neck collars made of expandable, non-heat-conducting plastic are very useful for larger birds such as geese.[16]

Some results

An Arctic Tern ringed as a chick not yet able to fly, on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast in eastern Britain in summer 1982, reached Melbourne, Australia in October 1982, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 miles) in just three months from fledging.

A Manx Shearwater ringed as an adult (at least 5 years old), breeding on Copeland Island, Northern Ireland, is currently (2003/2004) the oldest known wild bird in the world: ringed in July 1953, it was retrapped in July 2003, at least 55 years old. Other ringing recoveries have shown that Manx Shearwaters migrate over 10,000 km to waters off southern Brazil and Argentina in winter, so this bird has covered a minimum of 1,000,000 km on migration alone (not counting day-to-day fishing trips). Another bird nearly as old, breeding on Bardsey Island off Wales was calculated by ornithologist Chris Mead to have flown over 8 million kilometres (5 million miles) during its life (and this bird was still alive in 2003, having outlived Chris Mead).

Ringing activities are often regulated by national agencies but because ringed birds may be found across countries, there are consortiums that ensure that recoveries and reports are collated. In the UK, bird ringing is organized by the British Trust for Ornithology. In North America the US Bird Banding Laboratory collaborates with Canadian programs and since 1996, partners with the North American Banding Council (NABC).[17] The European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) consolidates ringing data from the various national programs in Europe.[18] In Australia, the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme manages all bird and bat ringing information.[19] while SAFRING manages bird ringing activities in South Africa.[20] Bird ringing in India is managed by the Bombay Natural History Society. The National Center for Bird Conservation CEMAVE coordinates a national scheme for bird ringing in Brazil.[21]

Notes

- ↑ Cottam, C (1956). "Uses of marking animals in ecological studies:marking birds for scientific purposes". Ecology 37: 675–681.

- ↑ Fisher, J. & Peterson, R.T. 1964. The world of birds. Doubleday & Co., Garden City, New York. 288 pp.

- ↑ Charles Knight (1842) The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: of the society for the diffusion of useful knowledge.Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) v.11 [n.s. v.2] (pp. 277-278)

- ↑ Schechter, Frank I. The Historical Foundations of the Law Relating to Trade-Marks. New York: Columbia University Press, 1925. p. 35

- ↑ J. Haffer (2007) The development of ornithology in central Europe. Journal of Ornithology. 148:125-153 doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0160-2

- ↑ Spencer, R. 1985. Marking. In: Campbell. B. & Lack, E. 1985. A dictionary of birds. British Ornithologists' Union. London, pp. 338-341.

- ↑ NABC 2001 North American / brightonBander's study guide. North American Banding Council PDF

- ↑ Wright, Earl G (1939) Marking Birds by Imping Feathers. The Journal of Wildlife Management 3(3):238-239

- ↑ WAYNE R. MARION, JEFF D. SHAMIS (1977) An annotated bibliography of bird marking techniques. Bird banding 48(1):42-61 [1]

- ↑ Rappole, J. H. and Tipton, A. R. 1991. New harness design for attachment of radio transmitters to small passerines. Á J. Field Orn. 62: 335-337

- ↑ Beat Naef-Daenzer (2007) An allometric function to fit leg-loop harnesses to terrestrial birds. Journal of Avian Biology 38(3):404-407 PDF

- ↑ Mikael Hake, Nils Kjellén, Thomas Alerstam (2001). "Satellite tracking of Swedish Ospreys Pandion haliaetus: autumn migration routes and orientation". Journal of Avian Biology 32 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048X.2001.320107.x.

- ↑ Yutaka Kanaia, Mutsuyuki Ueta, Nikolai Germogenov, Meenakshi Nagendran, Nagahisa Mita, and Hiroyoshi Higuchi (2002) Migration routes and important resting areas of Siberian cranes (Grus leucogeranus) between northeastern Siberia and China as revealed by satellite tracking. Biological Conservation 106(3):339-346 PDF

- ↑ Australasian Wader Studies Group: Wader flagging

- ↑ Kobe, Michael D. (1980) Detrimental effects of nasal saddles on male ruddy ducks. J. Field Ornithol., 52(2): 140-143 PDF

- ↑ USGS (2003) Auxiliary markers

- ↑ John Tautin and Lucie Métras (1998) The North American Banding Program. Euring Newsletter Vol 2.

- ↑ EURING

- ↑ ABBBS

- ↑ SAFRING

- ↑ CEMAVE

References

- Knox, A.G. 1982. "Ringing pioneer". BTO News No. 122, p. 8.

- Knox, A.G. 1983. "The location of the Ringing Registers of the Aberdeen University Bird-Migration Inquiry". Ringing and Migration 4: 148.

- Martin-Löf, P. (1961). "Mortality rate calculations on ringed birds with special reference to the Dunlin Calidris alpina". Arkiv för Zoologi (Zoology files), Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademien (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) Serie 2 Band 13 (21).

External links

- A1 ID Systems: Manufacturer of electronic bird rings. (Microchip identification for animals)

- LaB O RINg Project:Birds of Western Palearctic in Hand

- Report a found band in the United States

- Official US Bird Banding Lab

- Report ringed birds online from all of the European schemes

- EURING (Co-ordinating organisation for European bird-ringing schemes)

- Canadian Migration Monitoring Network (Co-ordinates bird migration monitoring (includes bird banding) stations across Canada)

- Types and sizes of bird rings used in Poland published by the Aranea, bird rings producer.

- The North American Banding Council (NABC)

- The Institute for Bird Populations - MAPS banding Program

- BBC News of Bardsey Island, ringed 1957

- Official CEMAVE-Brazil

- Calgary Bird Banding Society